By Dr Charles Margerison

Psychologist and author of Amazing People Learning.

This article provides an example of how one manager, called Chris, has worked to improve team problem solving. We started by discussing the prevailing situation.

“As a new manager in this organization, I found teamwork was undermined by harsh attitudes and chronic criticisms that some team members had for other people’s contributions

It was a tough place to work. Verbal punishment, often sarcastic and masked as false humour, was the order of the day. In particular, it was very hard on apprentices and junior team members,” said Chris.

“’How did you change that,” I asked.

“Well, I wondered if I should attack the negative atmosphere by criticising their approach. Instead, I said that I wanted a positive approach to problem solving. I focused my comments in meetings to praising those who showed positive thinking, when they based their opinion on evidence. I hoped that this would raise the level of our problem solving discussions,” he said.

In this article, I have summarized some of the ways that Chris, as the team leader, used to improve problem solving. Examples like this provide mini case studies of the leadership needed.

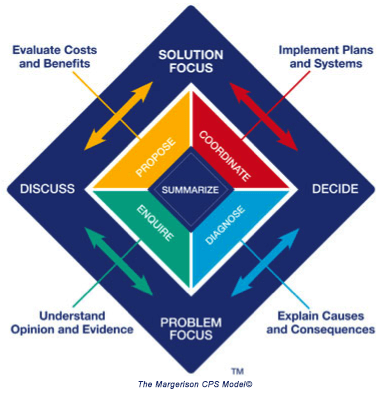

Chris was attending one of the workshops that I conduct on personal and business problem solving. I had introduced the five key skills of team problem solving, which forms a framework often referred to as the Margerison Communication and Problem Solving (CPS)® Model.

These skills are:-

Enquiry – involves setting questions and finding information to aid the understanding of a problem.

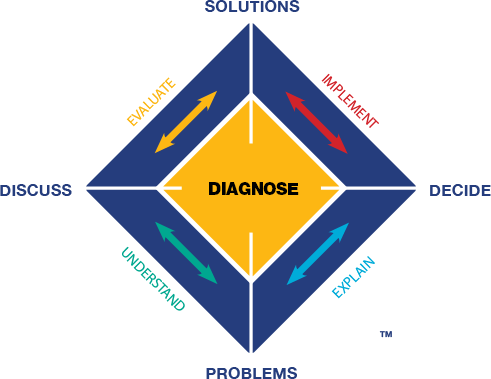

Diagnosis – involves analyzing data and explaining the causes and consequences of problems.

Summarizing – involves reviewing opinions and evidence, and providing the information gathered in a summary form for discussion.

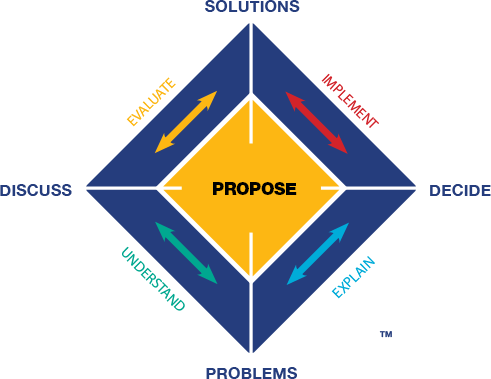

Proposing – involves generating ideas and assessing options to resolve problems.

Coordinating – involves taking one or more solutions and working with others, to plan and implement them.

Applications

In the discussion, on ways to use the five main skills, Chris outlined various cases and the issues arising. These notes represent an overview of the discussion.

Enquiry – Chris said, “I note in my team, there are more statements than questions. Also, the statements are often critical of others. Rather than research a problem, there is an inclination to rush to solutions. Therefore, I am encouraging those who are willing to ask questions and search for new information. I usually do that by saying it is a useful question. I also ask the person to indicate how they will collect evidence and then give them the green light to get on with the job. I ask everyone to give support, then I put the item on the agenda for the next meeting. That process of support shows my determination to foster useful enquiry that can help all of us.”

Diagnosis – Interpreting data and coming to relevant conclusions is vital to all problem solving. Chris explained that it was difficult to change attitudes, “If things go wrong, and they often do, the reaction is to get the technical operation going again quickly, rather than find the cause of the breakdown. I have encouraged team members to look at the attitudes and motivation of people, as that is crucial to understanding the issues. This is beginning to have an effect. We have noticed a decline in absenteeism and accidents, the more supervisors ask questions and gather information from those involved in the operational work.”

Proposing – Coming up with a range of solution options and assessing the best, takes time and skill. “I noticed in my team, when I arrived that there was a focus on the short term,” said Chris. “People who suggested new ideas were usually derided. Arguments replaced discussion. By giving permission and project funds to explore projects that last longer, I have encouraged a more proactive approach.”

Coordinating – Developing a plan of action based on evidence takes time and effort. Implementing the plan requires a systematic and determined effort. “Making sure output continued, even if short cuts on safety and maintenance happened, was how the team had operated,” said Chris. “I have now insisted that we take time to have well thought out plans. I write to team members and ask for their views in writing, and ensure everyone has time at the meetings to be heard.”

Summarizing – It is important that everyone knows who is doing what, why and when. Communicating so that all team members are involved, is crucial to gaining support. “Communication before I arrived was mainly verbal. Little was written down. Therefore, misunderstandings occurred on details, as there were lots of reasons why problems arose, but little evidence. I have asked everyone to summarize action steps and to let me have a copy for each project. In return, I share my comments. When I see good communication I write a note saying that it is helpful,” said Chris.

Overview

By introducing the team to the Communication and Problem Solving (CPS)® Model, Chris provided a focus point for the team discussions. In addition, the focus on the relationships, encouraged recognition and respect for all views. Building confidence amongst the less vocal members was important.

By introducing the team to the Communication and Problem Solving (CPS)® Model, Chris provided a focus point for the team discussions. In addition, the focus on the relationships, encouraged recognition and respect for all views. Building confidence amongst the less vocal members was important.

Chris did that by praising positive initiatives to improve the level of enquiry and diagnosis. In addition, more time was given for team members to follow up on points that needed investigation.

Having a systematic approach to problem solving and helping team members develop the five key skills began to have effect. Proposals for solutions were more carefully thought through. When action choices were made, time was allocated to assess the implications of action, before decisions were made.

Conclusion

Problem solving depends as much on the style of communication, as it does on the substance of the technical content. Ensuring both complement each other requires leadership, which gives team members permission to improve the quality of enquiry and diagnosis. It also requires praise to develop the confidence of team members when they make useful to contributions to both the analysis of problems and the solutions.

Effective problem solving is what everyone is paid to do. The Margerison Communication and Problem Solving (CPS)® Model provides a shared framework to achieve this. As a result, team members can assist colleagues by mutual support, particularly when under pressure for results.

Dr Charles Margerison, founder of Amazing People Worldwide and Amazing People Schools, is a Psychologist. As well as working in educational organisations for many years, he has consulted widely for major corporates in the fields of organizational and educational psychology. He was previously Professor of Management at Cranfield University, UK, and the University of Queensland, Australia. He founded Amazing People Worldwide in 2006 and is supported by a dedicated global team. Dr Margerison is a member of the Royal Institution, Royal Society of Literature, Historical Association, and Association of Business Psychology. He previously co-founded Emerald Publishing Ltd, and Team Management Systems, a team-building tool, which is now used in 190 countries worldwide.

Dr Charles Margerison, founder of Amazing People Worldwide and Amazing People Schools, is a Psychologist. As well as working in educational organisations for many years, he has consulted widely for major corporates in the fields of organizational and educational psychology. He was previously Professor of Management at Cranfield University, UK, and the University of Queensland, Australia. He founded Amazing People Worldwide in 2006 and is supported by a dedicated global team. Dr Margerison is a member of the Royal Institution, Royal Society of Literature, Historical Association, and Association of Business Psychology. He previously co-founded Emerald Publishing Ltd, and Team Management Systems, a team-building tool, which is now used in 190 countries worldwide.